The Poet’s Corner

by Russell Bittner

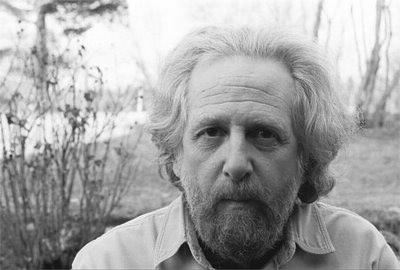

Interview with Baron Wormser

It was, quite by coincidence, Diane who introduced me to Baron. I Googled to his name and found “Exhilaration Blues” (which I’ve included below) at his Website. No slouch of a poet can write a piece like “Exhilaration Blues,” and I knew I had a winner. What I didn’t know is whether or not I had the stuff to convince him to participate.

He responded a couple of days later and told me he’d be happy to. (I frankly suspect it was more on the strength of Diane’s introduction than on whatever I may’ve had to say.) And so, here we are.

For starters, his encyclopedic bio:

RRB: Baron, let’s please first take a look at “Exhilaration Blues,” then let you fill us in on some of the background.

Baron, let’s please first take a look at “Exhilaration Blues,” then let you fill us in on some of the background.

“Exhilaration Blues” (Last Days of the Berlin Wall)

Everywhere

Gaping tourists:

Leicas, Nikons, Minoltas holding visual court.

As Uncle says,

Life’s become a spectator sport.

Even with the streets silly with people—

Matrons and barmen, butchers and teachers—

Someone’s trying to nudge history

A bit to the right or left for composition’s sake,

Diddling with the light, the drama of millimeters.

Someone’s explaining to the surprised

how there are no surprises.

Gretel was yelling her hidden soul out

For her Vater who tripped up in the mid-60s

And slit his wrists one quiet evening.

Meanwhile

Some guy tried the moves on her.

“You’re sweet goods under any ideology.”

“Thus, capitalism begins,”

She sniffed back at him.

Karl pronounced it the Woodstock of anger—

The way people frolicked,

that twitchy, beleaguered kick.

No stateside idealism,

the Hendrix waft of freaky hope,

This was edgier yet jolly too

like an air-escaping balloon.

On the mornings after, pensioners sifted the litter

for treasure.

Policemen prodded the embers of duty.

Two placards tumbled in the wind’s sigh:

“Brecht is dead at last.”

“Brecht can never die.”

Auntie told Gretel a dab of horseradish

in schnapps was the sovereign

remedy for a sore throat,

But Gretel said she didn’t mind

being hoarse. It was her passion

and it was her choice.

BCW: I’ve never been to Berlin. I’ve read a good deal, however, about the world of communism and—like millions of people—was moved by the events that brought about the end of the Wall. I’m not sure how this swam into my head, but I knew I wanted the paradox that’s in the title, the sense of this being at once an intoxicating and yet sobering event, the smashing of the chains and the awareness of the costs those chains exacted.

I’ve never been to Berlin. I’ve read a good deal, however, about the world of communism and—like millions of people—was moved by the events that brought about the end of the Wall. I’m not sure how this swam into my head, but I knew I wanted the paradox that’s in the title, the sense of this being at once an intoxicating and yet sobering event, the smashing of the chains and the awareness of the costs those chains exacted.

RRB: Believe me, Baron, as one who has not only visited, but who also once lived in Berlin (West), I can assure you that you’ve done well.

Believe me, Baron, as one who has not only visited, but who also once lived in Berlin (West), I can assure you that you’ve done well.

I must confess: finding jewels in your opus rather magnus is not an easy task. The mine goes on and on; the seams of gold are endless. I can take my favorites—quite arbitrarily, I might add—or we can take yours. You know what moved you to write a particular piece; I do not. I suspect that what moved you is at least as interesting to our readers as the piece itself—wouldn’t you agree?

I must confess: finding jewels in your opus rather magnus is not an easy task. The mine goes on and on; the seams of gold are endless. I can take my favorites—quite arbitrarily, I might add—or we can take yours. You know what moved you to write a particular piece; I do not. I suspect that what moved you is at least as interesting to our readers as the piece itself—wouldn’t you agree?

BCW: What moves me is hard to pin down. I believe that poets are mediums. We don't really know where the poems come from. We write down a draft and then go from there. Pretty much anything can set a poem off for me—a word, a memory, an image, something I read. So it's hard to pin down what moves me.

What moves me is hard to pin down. I believe that poets are mediums. We don't really know where the poems come from. We write down a draft and then go from there. Pretty much anything can set a poem off for me—a word, a memory, an image, something I read. So it's hard to pin down what moves me.

RRB: Understood.

Understood.

Baron, I found the following quote from you in what I believe was an essay you wrote titled “On Political Poetry,” which appeared in The Manhattan Review.

Baron, I found the following quote from you in what I believe was an essay you wrote titled “On Political Poetry,” which appeared in The Manhattan Review.

Whenever the topic of "political poetry" is raised, I find myself reflexively grating my teeth. The term posits a sort of detention area in which a certain sort of poetry is carefully segregated from other sorts of poetry. The implication is that the political nature of life, the fact that human beings live in societies and that political decisions are being made daily in those societies, in war and in peace, is not part of poetry per se. Poetry has better things to do than parse politics. This viewpoint seems callow but attractively American in that the aura of self-expression reigns more or less supreme. To make the political, and, of necessity, historical side of life part of the natural fabric of a poem poses a distinct challenge. The lyric, declarative self has other things to do such as writing about mom and dad. Who can argue the importance of mom and dad?

Whenever the topic of "political poetry" is raised, I find myself reflexively grating my teeth. The term posits a sort of detention area in which a certain sort of poetry is carefully segregated from other sorts of poetry. The implication is that the political nature of life, the fact that human beings live in societies and that political decisions are being made daily in those societies, in war and in peace, is not part of poetry per se. Poetry has better things to do than parse politics. This viewpoint seems callow but attractively American in that the aura of self-expression reigns more or less supreme. To make the political, and, of necessity, historical side of life part of the natural fabric of a poem poses a distinct challenge. The lyric, declarative self has other things to do such as writing about mom and dad. Who can argue the importance of mom and dad?

Would you care to elaborate on this paragraph before we move on to another poem? If you’ve already said as much as you care to say on the topic, that’s fine. I just think we all sometimes have additional (or even different) thoughts on an issue with the passage of time, and I don’t really know when you wrote and published this essay.

Would you care to elaborate on this paragraph before we move on to another poem? If you’ve already said as much as you care to say on the topic, that’s fine. I just think we all sometimes have additional (or even different) thoughts on an issue with the passage of time, and I don’t really know when you wrote and published this essay.

BCW: Our key political document is animated by the word “pursuit.” I can understand that word, but I wonder how much is lost by our refusal to admit the links that inform the past and that are present in each moment. Another way of saying this is that life isn’t all in front of us. The more we can feel our ties to the past and how they inform the present moment, the more human we can be in the sense of not being naïve or innocent or downright ignorant.

Our key political document is animated by the word “pursuit.” I can understand that word, but I wonder how much is lost by our refusal to admit the links that inform the past and that are present in each moment. Another way of saying this is that life isn’t all in front of us. The more we can feel our ties to the past and how they inform the present moment, the more human we can be in the sense of not being naïve or innocent or downright ignorant.

Quentin Anderson once wrote a book about American literature called The Imperial Self. To my mind, it’s a prescient title. He wrote about the sense of the American self as an encompassing force. This force plays itself out in all aspects of our American lives; our poetry is no exception. Bringing the past to life in the way that I do in a poem such as “Goethe in Kentucky (1932)” interests me a great deal. There’s something deeply unnerving about the American desire to jettison the past or caricature it via theme parks and such. Perhaps we hate being tied down to anything static. But the past isn’t static. It’s our crucial imaginative domain. Beyond the sheer facts—when the Civil War started—it’s as unsettled as the present moment.

RRB: Thanks, Baron, for the elaboration. And now, back to what brought us together in the first place: viz., your poetry.

Thanks, Baron, for the elaboration. And now, back to what brought us together in the first place: viz., your poetry.

I found your piece “Carthage and Airplanes” online. I’d first like to quote Stephen Dunn on this poem, then let our readers have a look at it, then let you give us the background.

I found your piece “Carthage and Airplanes” online. I’d first like to quote Stephen Dunn on this poem, then let our readers have a look at it, then let you give us the background.

Mr. Dunn (who, to date, has shown scant interest in participating in one of these interviews, though maybe that will change when he sees his name next to yours) had this to say about it: “(the poem presents) a replica of a president befuddled by events he's helped to create, yet cognizant enough to know that he can exercise enormous power...Through his droll and deft mediation and orchestration of effects, Wormser has imagined for us a man who's a frightening mixture of power and banality.”

Mr. Dunn (who, to date, has shown scant interest in participating in one of these interviews, though maybe that will change when he sees his name next to yours) had this to say about it: “(the poem presents) a replica of a president befuddled by events he's helped to create, yet cognizant enough to know that he can exercise enormous power...Through his droll and deft mediation and orchestration of effects, Wormser has imagined for us a man who's a frightening mixture of power and banality.”

For the benefit of our readers, let me say that “Carthage” is Baron’s chapbook of poems about a certain American President. “Carthage and Airplanes” is one of the poems in that chapbook. The “certain American President” is just one in a long line of American Presidents. My hope is that the poem will live longer than the correction and clean-up following this “certain American President’s” administration. My expectation? That it will.

For the benefit of our readers, let me say that “Carthage” is Baron’s chapbook of poems about a certain American President. “Carthage and Airplanes” is one of the poems in that chapbook. The “certain American President” is just one in a long line of American Presidents. My hope is that the poem will live longer than the correction and clean-up following this “certain American President’s” administration. My expectation? That it will.

On, then, to “Carthage and Airplanes.”

On, then, to “Carthage and Airplanes.”

Carthage likes to ride in airplanes.

Up in the sky he can forget

About the schedules of earth.

It is almost like thinking,

Gazing out the window at the clouds.

He likes to ponder.

"We're pretty high up," he says

To his aides.

"I wonder if we could go much higher."

Everyone looks thoughtful.

Back on earth ten-year-olds heft Uzis,

People drop dead on sidewalks,

Friendship sours like old milk.

How much better it is in the sky!

Too bad you have to be going somewhere.

Too bad the endless limo will appear

And some suit or turban or daishiki

Will greet you and start

Telling you about what's going

To happen soon or happened yesterday.

"Why don't you fly around more?"

Carthage would like to say to them.

If you live in the sky, nothing happens.

You don't even see the rain.

It is almost like thinking.

BCW: The character of Carthage resulted from a longstanding desire of mine to create a character that appeared in a series of poems. This desire stemmed in part from my admiration of the Cogito poems of Zbigniew Herbert. One night, I started writing this poem about a guy on an airplane. I realized fairly quickly who this guy was—George W. Bush. And yet, he was not George W. Bush. He was someone I’d made up who variously echoed the U.S. president, but who was his own man. Over a period of time, I was more or less possessed by the figure of Carthage. I self-published the chapbook because it would’ve taken forever to do it through conventional channels, and there was no telling whether conventional channels would even have been interested. It went through three printings.

The character of Carthage resulted from a longstanding desire of mine to create a character that appeared in a series of poems. This desire stemmed in part from my admiration of the Cogito poems of Zbigniew Herbert. One night, I started writing this poem about a guy on an airplane. I realized fairly quickly who this guy was—George W. Bush. And yet, he was not George W. Bush. He was someone I’d made up who variously echoed the U.S. president, but who was his own man. Over a period of time, I was more or less possessed by the figure of Carthage. I self-published the chapbook because it would’ve taken forever to do it through conventional channels, and there was no telling whether conventional channels would even have been interested. It went through three printings.

I suppose the poems are satirical in the sense that you grant a dolt his humanity, and yet realize that no one is always a dolt—and that doltishness has its reasons. If you or I sat across from George the Elder and Barbara for many years at the dinner table, who knows what would happen to us? It’s easy enough to demonize anyone. The complexity is more sobering and frightening. I seem to recall reading that Hitler had an interview scheduled for the position of opera set designer in Vienna, but that the director didn’t keep the interview. Hitler subsequently turned his attention to other matters. None of the circumstances excuse the behaviors, but they certainly give us pause for thought and feeling.

RRB: Good of you then, Baron, not to have painted a cartoon character.

Good of you then, Baron, not to have painted a cartoon character.

I’d like to leave the choice of the last poem to you. I could do it. I can do it. I would do it. And I will do it—but I’d still rather leave the choice to you.

I’d like to leave the choice of the last poem to you. I could do it. I can do it. I would do it. And I will do it—but I’d still rather leave the choice to you.

It’s your call.

It’s your call.

BCW: Then call it I will.

Then call it I will.

“Buddhism”

It’s about not-about. I’ll start again

And stop there—which is more like it.

The Via Negativa goes Nowhere

And that’s a lovely place—the empty lake

In front of the barren hotel where some timeless,

Karmic habitués look past one another.

Better five minutes of Zen than

A hundred books about Zen. Poems

Are another story. They too inhabit

No place gracefully, dwell

Offhandedly in mini-eternities.

They too welcome oblivion. Authorship’s

A ruse but that fades. Sit still again.

No nothing. You can feel it. Approximately.

RRB: Baron, do I detect a bit of tongue-in-cheek here? If so, then bravo! If not, then I’m the lesser fool.

Baron, do I detect a bit of tongue-in-cheek here? If so, then bravo! If not, then I’m the lesser fool.

BCW: Yes, I have a bit of tongue in cheek working in there. One of the beauties of Buddhism is that whatever one proposes can be unproposed, as it were. One of the beauties of poems is that one can build up a series of propositions that seem to move forward, but that don’t go anywhere special. Poems don’t prove anything; nor does Buddhism.

Yes, I have a bit of tongue in cheek working in there. One of the beauties of Buddhism is that whatever one proposes can be unproposed, as it were. One of the beauties of poems is that one can build up a series of propositions that seem to move forward, but that don’t go anywhere special. Poems don’t prove anything; nor does Buddhism.

RRB: And on that note, Baron, I wish you a very good night and thank you for your participation. It’s been a Buddhist blast.

And on that note, Baron, I wish you a very good night and thank you for your participation. It’s been a Buddhist blast.